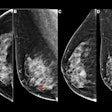

False-negative breast cancer screening rates are increasing over time, according to research published October 22 in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

A team led by Eniola Oluyemi, MD, from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD, also found that these increasing rates are tied to patient and screening facility characteristics. A personal history of breast cancer is the strongest patient-level factor associated with a false-negative result.

“The causes of the observed associations are unclear based on information available … although [they] may include variations in use of supplemental screening and in healthcare access in general,” the Oluyemi team wrote.

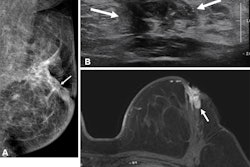

False-negative breast cancer screening exams can delay proper diagnosis, which may lead to worse clinical outcomes. However, the researchers noted challenges in systematically evaluating these exams due to the low incidence of interval breast cancers.

Oluyemi and colleagues used data from the American College of Radiology’s (ACR) National Mammography Database (NMD) to extract data about patient- and facility-level factors in order to study trends in false-negative exams and diagnostic mammograms. They included data collected between 2010 and 2022 from 38.3 million mammograms in 15.5 million women. Of the total mammograms, 32.2 million were screening exams, while the remaining 6 million were diagnostic exams.

The team reported that, overall, the false-negative rate for screening and diagnostic mammography per 1,000 exams was 1.9 and 4, respectively. The screening false-negative rate per 1,000 exams increased consistently across the study period, from 0.7 in 2010 to 2.5 in 2022. This included a maximum value of 2.5 in each year from 2020 to 2022.

The researchers also performed multivariable analysis for screening exams. They found that the likelihood of a false-negative exam was lower for race categories other than white (odds ratio [OR] = 0.3 to 0.95). For diagnostic exams, the likelihood was lower for Asians (OR = 0.91), Hawaiians (OR = 0.77), and Hispanics (OR = 0.7). However, it was higher for Black women (OR = 1.12).

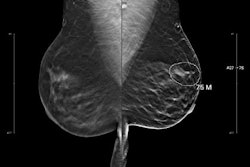

For other factors, the likelihood of a false-negative screening exam was higher for the following: breast density categories other than almost entirely fatty breasts (OR = 1.6 to 2); women with personal (OR = 3.69) or family (OR = 1.29) history of breast cancer; and academic or university-based facilities (OR = 1.37).

For diagnostic exams, the likelihood of a false-negative was higher for heterogeneously (OR = 1.46) or extremely (OR = 1.86) dense breasts. It was also higher for women with a personal (OR = 7.82) or family (OR = 1.31) history of breast cancer and for academic or university-based facilities (OR = 1.37).

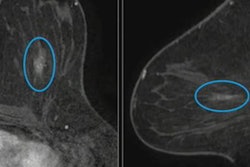

The study authors suggested that growing use of supplemental breast imaging screening via MRI or ultrasound could be driving false-negative rates. However, they added that the cause of the “observed temporal pattern” is uncertain from available data.

The authors called for future studies to find potential causes of these trends, noting that these studies could help inform quality assurance to reduce the risk of delayed breast cancer diagnoses.

Read the entire study here.